In 1891, an outbreak of Typhoid fever, traced to a contaminated well, forced the School to shut down for almost a month. Eight years later in 1899, the School closed again when there was an epidemic of what was called cerebro-spinal meningitis. On Monday, March 27 of that year, the boys left School in two special coaches that were attached to the 11:00 a.m. train to Baltimore. Each boy carried with him a letter from Principal Sidney Moreland. In it, he assured parents that they “may receive their sons without apprehension.” He said there was no danger that the boys would give the disease to any one at their homes because it thrives “only where great numbers live in close association.” He also said if they could not “conveniently have their sons with them,” they could send them back to School.

The Great Influenza of 1918

In 1918 when the influenza epidemic tore through Baltimore, the School’s remote location helped serve as a buffer against the spread of the deadly disease. Nevertheless, the first cases on campus were reported on October 5 — Visiting Day.

According to an article in The Week, in light of the illness, Headmaster Morgan Bowman “thought it best for the people to stay in the open as much as possible” so, to the disappointment of the students there was no dancing or any amusement for the visitors. By October 9, six more cases had developed, the infirmary was filled to capacity, and the School was closed by order of the health authorities. And as one reporter for The Week noted, “We have our mouths and noses sprayed twice a day as a precautionary measure.”

“School Reopens” was the headline in the October 26, 1918, issue of The Week, but there was more to the story. Reporter Oswald Eden wrote, “The quarantine was lifted on the 20th as far as going to school is concerned. But nobody will be allowed to go off the place, and nobody will be allowed to come on the place, for some weeks yet. No boy will have leave to go to town until the situation in Baltimore has become better.”

The Week also reported that several children of farm employees had a “touch” of the flu. “The most serious outbreak was in the family of Milton, the indispensable dining room and kitchen assistant, who lives in one of the houses at McDonogh Station. His seven young children all had the ‘flu’ and their mother also had double pneumonia and died of it on October 20.”

By the end of October, all the boys who had the flu had been discharged from the infirmary and the School was hopeful that the epidemic was gone for good and quarantine would be lifted. But another case developed and the “spraying of students” resumed. Finally, after more than a week with no new cases, the quarantine ended on November 9. “Now our people are allowed to come out to McDonogh on Sundays,” proclaimed a report in the November 16 issue of The Week. The report continued, “Following the raising of the quarantine on Saturday there was a throng of visitors at the school on Sunday. Mothers and sisters and cousins and aunts who had not seen the boys for weeks were here in force.”

Sadly, that was not the end of the story. Several months later, the flu took the life of a student, Durbin Billmire. Two weeks after Durbin’s death, William Ballard Smith, a faculty member since 1887, also succumbed to the flu after a 10-day illness.

COVID-19

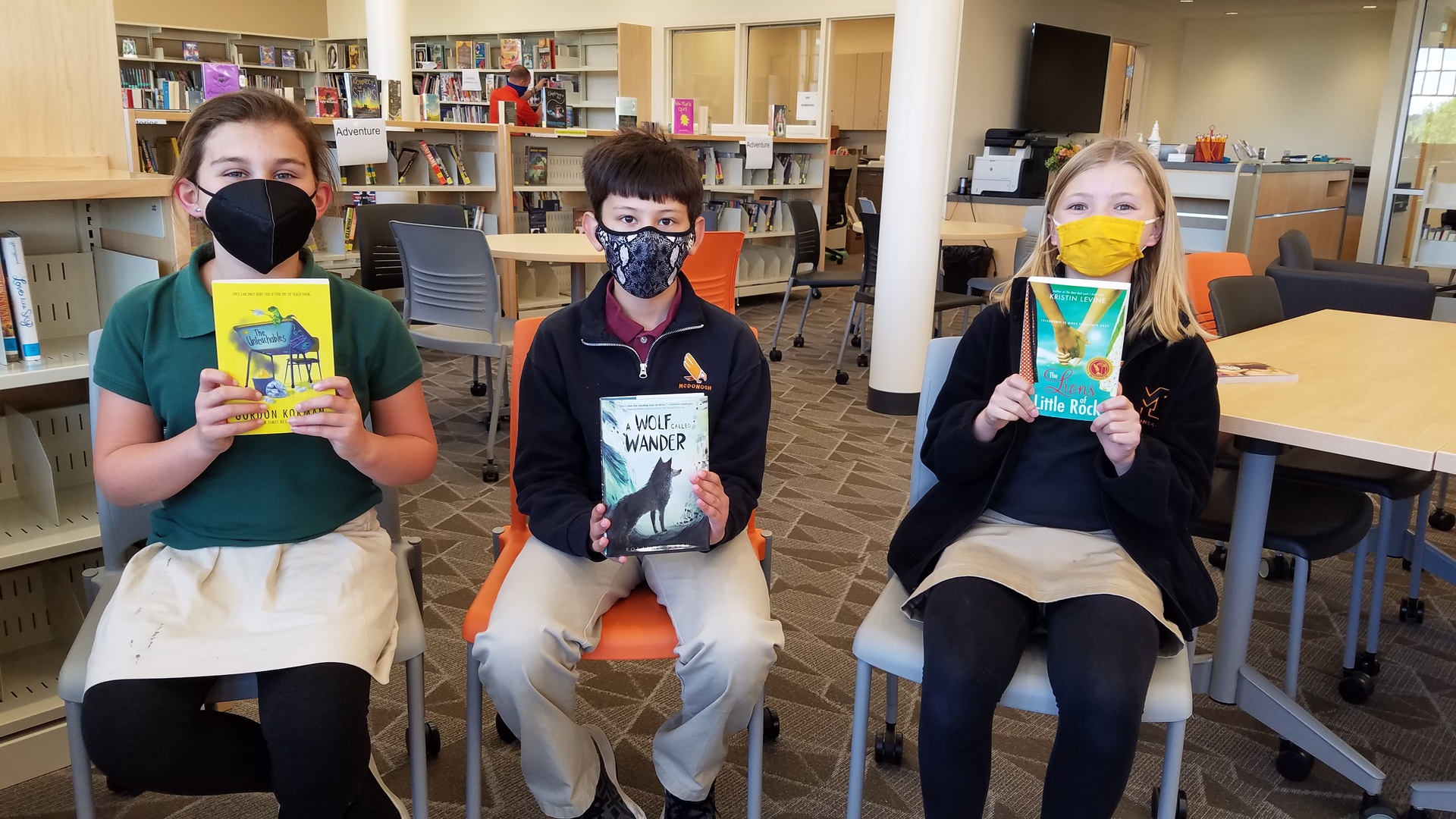

At the beginning of 2020 when COVID-19 began circulating, McDonogh convened what became known as the Coronavirus Task Force. The group of administrators, medical professionals, and the School’s communications expert met every 48-72 hours and developed a plan to transition more than 1,400 students in prekindergarten to twelfth grade to distance learning. When the pandemic hit, McDonogh was prepared and made sure every student had access to a computer, laptop, or iPad. On Thursday, March 12, students left School with their books, devices, musical instruments, and anything else they thought they may need for the temporary closure. The following day, the United States declared the COVID-19 outbreak a national emergency.

What was anticipated to be a few weeks of virtual school turned into months. As Director of Innovation and Learning Kevin Costa said,” Before too long, we were all getting used to the “Brady Bunch” tiles of Zoom, using tech platforms like Flipgrid, Nearpod, and EdPuzzle, and perfecting how to share screens. We were learning what worked, and we were also experiencing what was hard about virtual school. Nothing could have prepared us for how much we missed each other. We longed for an ordinary day when we’d start class with relationship-building questions like, “What’s for lunch?” or “How was your weekend?” — the millions of day-to-day conversations that make school, well, school.”

School reopened in the fall of 2020 under a hybrid (in-person and virtual) model in which half of the student population was on campus every day, while the remainder learned remotely. By early 2021, the full complement of students, faculty, and staff were back.